The impact of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on: Newton-le-Willows 1821-1851

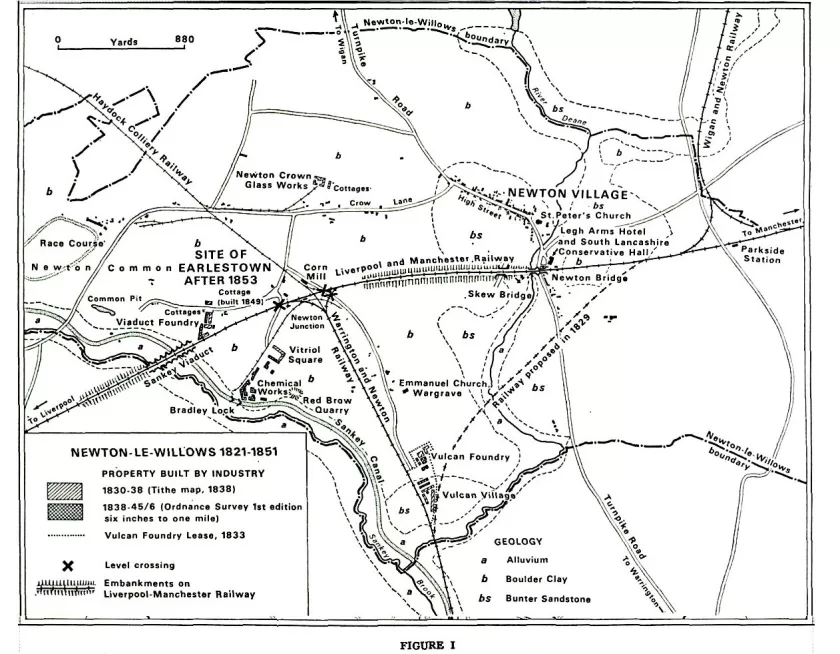

Newton le Willows is situated on the lowlands of south Lancashire, on the route to the north by way of Warrington, Wigan and Preston. From Saxon times until 1830 the village of Newton was in the east of the township, situated on an inlier of bunter sandstone overlooking a crossing place on the River Deane; this sandstone area provided a dry site and a water supply from shallow wells. The remainder of the township is a broad spread of boulder clay alluvial tracts limited to the stream courses, which find their way southwards to the Mersey. Most of the area is not subject to flooding. (Fig.1)

Between 1559, the date of its creation as a borough sending two representatives to Parliament, and 1830, Newton-le-Willows experienced few events of any significance. The township was visited by armed groups from both sides during the Civil War and there were skirmishes in the area, including the Battle of Winwick Pass or Red Bank to the south in 1648. In 1660 Richard Legh purchased the barony from Sir Thomas Fleetwood and gained control of the parliamentary borough.(2) Richard Legh was elected Member of Parliament for Newton in the year of the purchase.

The old chapel in the village, founded in 1242, had fallen into disuse and Richard Legh began to rebuild it in 1682.(3) Two years earlier horse racing on Newton Common, at the west end of the township, was recorded for the first time.4 Newton had become a prosperous market town by the end of the seventeenth century; this prosperity continued throughout the eighteenth century. The opening, in 1757, of the Sankey Canal, which ran along the western boundary of the township appears to have had no measurable effect upon the economic life of the township.

In sharp contrast, the surrounding towns of south Lancashire experienced considerable change in the eighteenth century. Warrington developed as a port on the Mersey after 1694 with

important sail cloth and textile industries, metal using industries including locks, hinges and pins, copper smelting, glass making and sugar refining. Wigan on the River Douglas, made navigable in 1 7 I 9, was a growing centre for coalmining and cotton manufacturing. After 1770 the area at the head of the Sankey Canal developed the industries of copper smelting, plate glass making and iron founding; from this industrial and urban sprawl was to emerge the town of St Helens. All these towns grew because they offered to entrepreneurs what Schumpeter described as ‘the necessary and sufficient conditions’5 for industrial development; these conditions include land, transport facilities and accessible raw materials. Unlike its neighbours, Newton-le-Willows in 1830 was still a small market town, and soon, in 1832, to lose its parliamentary franchise. A directory of this period gives the trades of the population as blacksmiths [2], boot and shoe makers [4], butchers [3], coal masters [1], corn millers and corn and flour dealers [2], glass manufacturers [1].(6) It was, in fact, merely a market town consisting ‘of one broad street distinguished by its numerous public houses’.(7)

On Wednesday, 15 September 1830, in this township an event of great national importance was witnessed: the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. To one person writing in the same year it seemed that prosperity was near: enthusiastically he wrote, ‘a new railroad to Warrington is about commencing which, when united with the Liverpool and Manchester railway, will much increase the business of the place’ (8) Nor was this all, for the Wigan Branch Railway from Parkside to Wigan was to be opened in 1832. To an imaginative person of that time it might have seemed that Newton was destined for a great future.

THE EFFECT ON THE ECONOMY

The building of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and the two other railways which joined it from the south at Newton Junction and from the north at Parkside gave Newton railway links with the growing cities of Liverpool and Manchester; later, in the 1830’s, links with Birmingham via the Grand Junction Railway and London were established, and with Wigan and Preston. By 1834 Newton had more railway connections than any other township of its size and could boast three railway stations Newton Junction, sometimes called Warrington Junction, Newton Bridge and Parkside.

The necessary and sufficient conditions for industrial develop ment appeared almost overnight. The economy of the township experienced change with the establishment of four industrial firms and each in its way made some contribution to the settle ment pattern. Their foundation was directly attributable to the railways:

“The Liverpool and Manchester railway, which passes through the chapelry, has no doubt been instrumental in inducing the proprietors of the several works to establish themselves here, and the Warrington and Wigan railways, connected with the great parent line, and that with Newton afford additional facilities for the conveyance of goods and persons.(9)”

The four companies created factory villages or as Dr J. D. Marshall has called them industrial colonies. Marshall has classified them as primary and secondary types, those at Newton were secondary being developments away from, or parallel to, that of a pre-existing town, perhaps before ultimate absorption in the latter. Secondary colonisation, as seen in these terms, was com mon in industrial Lancashire.(10)

In 1830 two companies were established; it is difficult to decide which came earlier for convenience the Chemical Works will be examined first. On the east bank of the Sankey Canal, at Bradley Lock, James Muspratt began the production of soda by the Leblanc process. It was a particularly convenient site since, by the Sankey Canal Act of 1755, limestone was accorded freedom from dues, a concession which, when coupled with the nearness of coal-mines, made this site at Newton particularly advantage ous.11 Furthermore, salt was easily imported by Canal from Cheshire. (Fig.1) Very slowly a small settlement was developed by the chemical works around three sides of a square, called rather imaginatively Vitriol Square. It was not a mushroom growth and, as the map shows, only the north side had been com pleted by 1838, the remainder being built after that date. (Fig.1) In addition to the cottages, a small school was provided which also served as a church.

In the same year as Muspratt began soda production, the Vulcan Foundry was established. To the south of the works began to appear the first of a collection of terraced houses, owned by the Company, which now comprise the Vulcan Village. Their origin is somewhat obscure, one theory being that the Village was built by George Stephenson … to house railway workers, when the line between Manchester and Liverpool was being constructed.(12) A similar origin has associated the early years of the Village with the contractors’ men engaged on the construction of the colliery line, which was later replaced by the Warrington and Newton Railway, and that the houses were subsequently bought by Tayleur who sited his works alongside them.(13)

Both theories are probably incorrect since, as Figure 1 shows, the Village was not completed by 1838, some seven years after the opening of the railways mentioned. Of course, the part in existence at that date may have been built by the Warrington and Newton Railway Company the records of which are missing, but there is no mention of a village in the minutes of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company. However, the shape of the Village is somewhat unusual, tapering southwards to a point; this can be explained by the shape of a lease of land to Tayleur and Stephen son on 30 May 1833, which has been added to Figure 1.

The plan attached to this lease also shows a small foundry, but no village. It seems safe to suppose that this village was built by the Vulcan Foundry Company, and forms the second contribution by in dustry to the growth of the town. As at Vitriol Square, a school room was built and a church soon after. A similar foundry was established three years later, alongside the Liverpool and Man chester Railway, by Messrs Jones, Turner and Evans. It was called the Viaduct Foundry. Here, too, a collection of workmen’s houses grew up, and again they were not all built at once. (Fig.1) The fourth of these firms, to which earlier reference was made, embarked upon the manufacture of crown glass, on a large scale.(14)

Ackers, Abraham and Company’s works were founded upon land to the north of Crow Lane, a site which was to be used by various glass firms until the early years of the present century. The firm, however, built only a single row of workers’ cottages. (Fig.1) One other small industrial enterprise appeared between 1830 and 1835. This was a Com Mill alongside the Haydock Colliery Railway; it was started by James Fairclough, but an industrial colony did not emerge.

The Tithe Survey map of 1838 provides a good picture of the township at that time. (Fig. 1) To the north-east was the old village of Newton which had changed hardly at all; to the west and the south-west were the four industrial colonies. At three of these the settlements were not complete-a reminder of the small ness of these undertakings in their early years. (Fig. 1) Such accommodation was bound to be necessary, for rural Newton could not be expected to provide either men skilled in engineering and alkali production or accommodation for those who had to be ‘imported’. In consequence, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway recommended ‘that two cottages be built at Newton Bridge Station for the use of Edward Griffiths, the Company’s Agent there, and for one of the Coach Porters, houses being very scarce and difficult to be got at Newton’.(15) It is interesting to note that by 1845, although the building of small housing estates by the established industries had been almost completed, there had been no noticeable addition to the settlement pattern by any other individuals, or groups of individuals. The village of Newton had changed very little since 1830, and over the rest of the town ship no noticeable intensification of settlement had taken place, except in the new single-industry communities,

The old village of Newton was also affected by the building of the railways. Even before the Liverpool and Manchester Railway had been completed, Thomas Legh, the lord of the manor, had opened a public house called the Legh Arms alongside the line at Newton Bridge station. The railway company objected to the sale of intoxicating drinks to passengers and trade declined.

In 1835, Newton having become the centre of a new constituency, the South Lancashire Conservative Hall was built behind the Legh Arms. It was rarely used and in 1846 it was leased by George McCorquodale who established a printing works.

In 1854 he leased the Legh Arms hotel. Newton was chosen because of the available premises and the central position of the place on the London and North Western Railway Company’s system. McCorquodale soon acquired contracts to print the railway company’s stationery and timetables.(16) At this time the printing company did not build any housing.

By 1845, when the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was being absorbed into the new London and North Western system, the facilities offered by the original line had already stimulated four industrial colonies. None had triggered off more continuous long-term urban growth, rather the centre of gravity of settlement was pulled away from an already existing centre. (17)

POPULATION.(18)

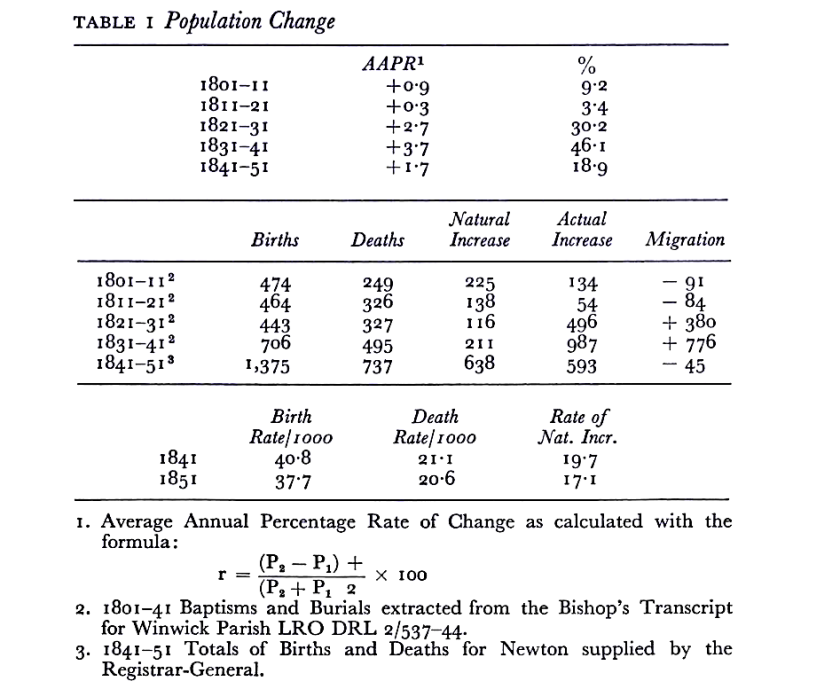

The four companies required a labour force which was not readily available in Newton; hence the need to build housing to attract and keep workers. The result was that the population of the whole township grew. It is apparent from Table 1 that population growth accelerated after 1830. The building of the Liver pool and Manchester and Warrington and Newton Railways attracted workers, some no doubt of a transitory kind, e.g. navvies, and building had started on the chemical works and the Vulcan Foundry.

The first jolt in population growth occurred between 1821 and 1831 when the average annual rate was 26 per cent or 30.2 per cent for the decade. The period of greatest growth was from 1831 to 1841 with an average annual rate of 3.7 per cent or 46.1 per cent over the ten years. In the decade 1841-51, when there was no significant industrial development the average rate of growth fell to 1.7 per cent per annum or 18.9 per cent for the ten years.

The components of population change are natural increase and migration. By using data from the transcripts of the Newton parish registers probable trends can be shown, but the true picture is understated and the data must be treated with caution. After 1841 data supplied by the Registrar-General has been used. The data in Table 1 suggest that the sharp increase in population in the decades 1821-31 and 1831-41 was the result of inward migration. This follows the general pattern of nineteenth century urban growth with labour being attracted towards work. In the second decade it is likely from the proportion of Irish recorded in 1851 that the ‘push’ of the Potato Famine had some influence. In general it would seem that ‘the motive force controlling the migration was the positive attraction of industry rather than the negative repulsion of agriculture.(19)

The decade 1841-51 when the first reliable data becomes available, there was slight out- migration. This data also permits the calculation of reliable crude birth and death rates, which show that the fertility of Newton’s population was high and similar to that of other towns in the area. Associated with a relatively low mortality rate, this produced a high rate of natural increase.

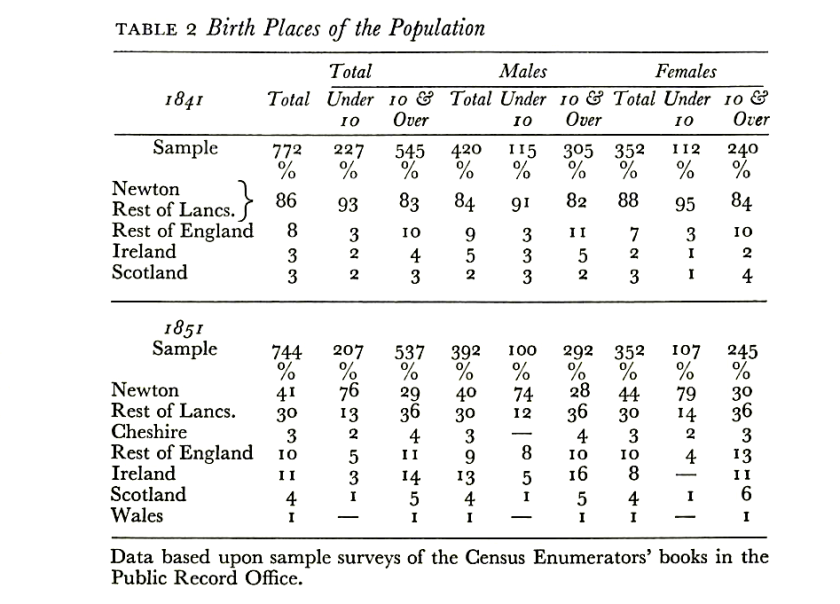

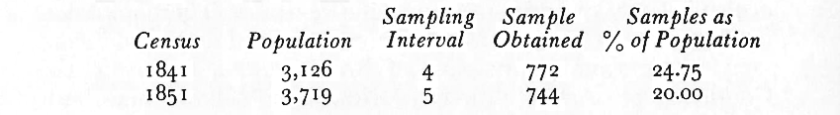

It would appear that between 1821 and 1851, due to the building of the railways and the industrial villages, Newton had experienced a short cycle of growth. The origins of the population indicate considerable migration into Newton between 1821 and 1851. The results of sample surveys of the Census Enumerators’ books for 1841 and 1851 appear in Table 2. In 1841 the data for place of birth is less extensive than in the later census.

It is only possible to show the proportion of those born in Lancashire and not separately in Newton; the proportion was 86 per cent. The non-Lancashire element (14 per cent) is interesting; the remainder of England provided 8 per cent and 3 per cent each from Ireland and Scotland. The proportions were slightly higher among those ten years and over.

In 1851 the proportion of Lancashire born had fallen to 71 per cent; 41 per cent had been born in Newton and 30 per cent came from the remainder of the county; the proportion of Newton born under ten years was very high, 76 per cent. The proportion of those born in the remainder of England had increased from 8 per cent to 13 per cent; 3 per cent came from neighbouring Cheshire. The Irish element had increased to 11-14 Per cent of those over 10 years and 16 per cent of males over 10 years.

Closer examination of the Census Enumerators’ books for 1851 reveals that the non-Lancashire element were distributed un- evenly in the various industrial villages. The majority of the Irish, particularly the males, were employed as chemical labourers at the chemical works, living in or near Vitriol Square; 50 per cent of them were lodgers. The Irish, as in other parts of Lancashire, were employed in unskilled jobs, whereas the Scots were in skilled occupations either as engineers at the Vulcan Foundry or printers at McCorquodale’s in Newton Village. Some of those over ten years old from other parts of England included, at the glassworks, a handful of glass makers and others in the glass trade, from Nailsea in Somerset, Oldbury and West Bromwich in Stafford- shire and Stourbridge in Worcestershire. The Nailsea tradition was continued for most of the nineteenth century with the manufacture, usually as a by-product from the molten glass at the end of the day, of small glass ornaments and novelties called ‘Nailseas’. Individuals included the manager of the chemical works, Charles A. Kelly, aged 27, from Bermondsey, and at the Vulcan Foundry there was a Daniel Papps, who was described as an engine erector and designer from Painswick in Gloucestershire. Also at the Vulcan were two Germans: Henry Dubs, aged 35, was an engineer, who later worked for the Bayer Peacock locomotive works at Gorton, Manchester, and the North British Works at Glasgow. William Strecker, aged 22, was described as an engineer also.

OCCUPATIONS

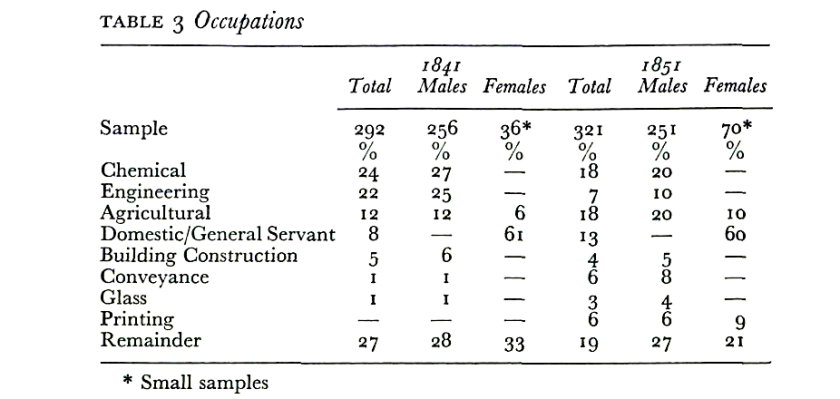

The occupation structure of Newton changed and occupations new to the township appeared. Table 3 shows that in 1841 chemical manufacturing and engineering were the main types of employment for men 27 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. The third largest employer was agriculture with 12 per cent of men and 6 per cent of women. Bearing in mind the small sub- sample for women, 61 per cent were employed in domestic service. Ten years later the pattern had become more diversified. The proportion of men employed in chemical manufacture to engineering had declined to 20 per cent and 10 per cent respectively. The fall in the proportion of those in engineering may partly be explained by the fact that in 1850 the Viaduct Foundry was in financial difficulties and trying to sell the works and cottages. (20) Agricultural work accounted for 20 per cent of male workers and was in joint first place with chemical manufacturing.

This suggests that agriculture in the area was prosperous; it is not surprising in view of the growing population not only in Newton, but in all the surrounding towns. Printing, a new industry, had appeared, providing work for 6 per cent of men and 9 per cent of women.

Employment figures for 1841 and 1851 indicates that within twenty years Newton had evolved a mixed economy of chemical manufacturing and engineering with smaller pockets of glass making and printing. With one fifth of the male working population employed in agriculture, Newton had become another piece in the emerging patchwork of industrialisation in South Lancashire.

SOCIAL

It is a concomitant of any settled community that it develops social institutions to meet its needs. Education was provided on an ad hoc basis in the early nineteenth century and in two of the industrial colonies schools were provided. At Vitriol Square a school was eventually built in the early 1840s and in the Vulcan Village a school was built in 1839. There was in the old village of Newton a number of schools including a Free Grammar School dating from 1699, two Dame Schools and a Sunday School started by the Reverend Peter Legh in 1823. (21)

As the population grew the organisation of the Church of England was unable to cope. Newton, in common with many townships and villages in central south Lancashire was part of the large medieval parish of Winwick. The Rector of Winwick, the Reverend J. J. Hornby, wished to divide the large parish into smaller manageable parishes. In 1841, the Winwick Rectory Act (22) was passed and Newton became a separate parish. However, the old chapel of St Peter’s at the east end of the village did not become the parish church. Edward, fourteenth earl of Derby, was the patron of Winwick and wished to become patron of the new parish church of Newton. The lord of the manor, Mr Thomas Legh, was patron of St Peter’s and was unwilling to transfer his right to the earl of Derby. (23)

The Stanleys had considerable political influence at this time. The fourteenth earl, who in 1841 was Sir Robert Peel’s Colonial Secretary, and who later became prime minister three times, was a formidable opponent. Due to his influence a new parish church was built near the new industrial village at the Vulcan Foundry, called Emmanuel Church, Wargrave. It was consecrated in 1843, and the patronage was invested in the earl of Derby.

LANDSCAPE AND MORPHOLOGY

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway crossed the township of Newton from east to west; for almost a mile between Newton Junction and Newton Bridge stations it passed through open country on an embankment. It was broken twice by a viaduct of four arches where it crossed the river Deane and the turnpike road to Warrington, and by a narrow skew bridge across a country lane between the old village and Wargrave. The embankment, about thirty feet high, must have been a striking feature in this flat rural area. It is still a barrier today. (Fig. i)

At the west end of the township the railway had to cross the Sankey Brook and Canal. George Stephenson achieved the cross- ing by means of a nine-arched viaduct from the steep eastern bluff of the valley to an embankment which carried the line westwards. The ‘Nine-Arches’ tower some seventy feet above the valley floor.

It has been asserted that: “This is not merely the first such great work of the railway age proper but a prototype for a form of structure which was to be repeated a thousand times over before the end of the century, which was not to be finally outmoded by new designs and methods until after the first world war, and which remains as characteristic of the English landscape as do her church spires and last hedgerows”.(24)

The Sankey Viaduct was the outstanding structure of the line and for a time it attracted many sightseers, which the railway company was quick to encourage and exploit. Trips to the Viaduct were run each day. Only five weeks after the opening of the railway in mid-October 1830, Maria Edgeworth, an indefatigable traveller and prolific letter writer of the early nineteenth century wrote:

“We were invited by Mr. Hodgson (25) … to go on the Liverpool railway in the very carriage in which the Duke of Wellington went. We ascended the very step ladder off which Huskisson fell and we got into a fine crimson canopied car. . . . Our carriage was sent on to meet us about 13 miles from Liverpool at a place called the Viaduct. Red paper tickets were put into our hands on getting into the cars on which were printed Trip to the Viaduct.

You are to comprehend that a regular communication goes on now by trains of cars on this railroad backwards and forwards to Liverpool and Manchester. . .. Independently of these regular trains the proprietors make use of these gala cars which they have fitted up for the Duke and the show of the opening and every day they go on with this ‘Trip to the Viaduct’ with their red tickets for whoever wishes to have a ride five shillings apiece there and back. And every day for these 5 weeks every one of the 4 cars have been crammed full of Liverpool ladies and gentlemen all dressed as for a fete. Even this makes money. [On arrival at the Viaduct] We saw the canal of the Sankey Navigation running below us and pretty sail boats. Oh the sail boats have all the beautyl [Afterwards, while waiting for their carriage the party ate] a dinner of bread and butter and cheese at a cottage Alehouse by the roadside..(26)“

Although the Sankey Viaduct was impressive, some of the materials used in its construction were produced locally, and this affected in a small way the landscape. On 27 January 1827, over three and a half years before the line was opened: “Mr. Gladstone reported that Mr. Stephenson recommended the immediate making of bricks on Newton Common, with a view to the building of the Sankey Viaduct, and the Bridge at Newton. Resolved: That the Land Committee be empowered to make the necessary arrangements and to contract for the making of such quantities of bricks for the above and other purposes on the Line of the Road as they may deem expedient.(27)“

The quarry from which the clay and sand was removed filled with water and until the nineteen fifties was known as the Common Pit. (Fig.1) Also along the Sankey Valley there are a few quarries from which sandstone is reputed to have been taken for facing the viaduct.

The railways of Newton were superimposed upon an existing pattern of roads. Local traffic on these increased with the development of the industrial colonies and problems occurred when road traffic crossed railway lines. There were three of these trouble spots. The road from the Vulcan Foundry to Newton Junction crossed the curve line to the Warrington and Newton line and the main line; the latter was also crossed again by a road leading to the chemical works. (Fig.1)

The morphology of the industrial colonies was affected by the railways, particularly the Vulcan Village. In 1829 a railway was proposed from south of the village to run north eastwards to join the Liverpool and Manchester line at Newton Bridge station. (Fig.1) This line was never built but its alignment influenced the shape of land leased for the village and the foundry. As the village was built in the fifteen years which followed it was fitted into this plot with its street plan tapering towards the south end. (Fig.1)

At the Viaduct Foundry the works and the early cottages were located between the Liverpool and Manchester line and Pepper Ally Lane. Only in 1849 was a new row of cottages built on the north side of this lane opposite the earlier dwellings. The Haydock Colliery Railway aligned north-west to south-east and the Liver- pool and Manchester line running east to west formed a wedge- shaped piece of land on which, after 1852, the railway town of Earlestown was to be erected. The major constraints on the morphology were laid down over twenty years earlier. (Fig.1)

From the passing of its Act of Parliament in 1826 until the merger into the London and North Western Railway in 1844, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was an important factor in changing the nature of Newton-le-Willows from a market town into a collage of industrial enterprises and settlements. This rail- way and the other lines provided entrepreneurs with the necessary and sufficient conditions for industrial development. It required the organisation and enterprise of such entrepreneurs to exploit these and generate industrial and urban growth. The industrial colonies were new factories and settlements thrown across the rural part of Newton by profit-maximising entrepreneurs. The role of these entrepreneurs must not be underestimated; the Liverpool and Manchester railway itself was created by a group of entrepreneurs who took considerable risks. Fundamentally they were organisers; ‘their distinctive characteristic was they fulfilled in one person functions of capitalist, financier, works manager, merchant and salesman.(28)

The efforts of the entrepreneurs had a considerable impact upon Newton-le-Willows between 1821 and 1851. The pre- dominantly rural landscape was changed by the appearance of the railways and especially the Liverpool and Manchester’s spectacular arched viaducts and embankments. The industrial firms introduced new technologies, occupations, an industrialised way of life and sharply altered the settlement pattern which had evolved slowly over the previous nine centuries. The population increased by natural increase and migration, the latter introducing new people from many parts of Britain and a few from the Continent of Europe. In 1851 Newton-le-Willows had been changed markedly and was well on the way to complete industrialisation; this was to be achieved in the second half of the century. In its small way this analysis of Newton-le-Willows between 1821-1851 illustrates the view of H. J. Fleure: “the growth and character of villages and towns and of their mutual relations is full of interest for those who will think of them in terms, not only of site and statistics, but also of the play of variously conditioned human minds.(29)“

NOTES

- ‘By resolution of the Council, dated 10 January 1939 . .. the name of the Urban District was changed from Newton-in-Makerfield to Newton- le-Willows, as from I March 1939, under the provisions of 8.147 (0 °f the Local Government Act 1933.’ Newton-le-Willows U.D.C. Year Book 1939-40, p. 7. During the nineteenth century the name was often, spelt Newton-in-Mackerfield as in the Act of 1855 18 & 19 Vie. Cap. 100.

- Lady Newton, The House of Lyme from its foundation to the end of the Eighteenth Century, 1917, p. 217.

- Ibid. p. 314.

- Ibid. p. 304.

- J. A. Schumpeter, Business Cycles A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process, 1964, p. 11.

- Pigot & Co., Northern Directory 1834, pp. 495-6.

- Stephen Reynolds Clarke, The New Lancashire Gazetteer or Topo- graphical Dictionary, 1830, pp. 125-6.

- Ibid.

- Northern Directory, op. cit. p. 495.

- J. D. Marshall, ‘Colonisation as a Factor in the Planting of Towns in North-West England’, in The Study of Urban History, ed. H. J. Dyos, 1968.

- D. W. F. Hardie, History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes, 1950, p. 12.

- The Earlestown and Newton News, i September 1956.

- Built By Stephenson, 1957, p. 13. Published by The Vulcan Foundry Limited.

- Northern Directory, op. cit. p. 495.

- Minutes Liverpool and Manchester Sub-Committee, 15 September 1836, p. 167.

- J. H. Lane, Newton-in-Makerfield Its History with Some Account of its People, 1914, pp. 77-91.

- J. D. Marshall, op. cit. pp. 217-18.

- In order to obtain data about place of birth and occupation, samples have been taken of the census enumeration books for 1841 and 1851 in the Public Record Office. Savings in time and labour are the main reasons for using sampling techniques. The samples have a 95 per cent confidence level and a reliability of ± 3 per cent.

- A. Redford, Labour Migration in England 1800-1850, ed. W. H. Chaloner, 1964, p. 70.

- Minutes Grand Junction Works and Estates Sub-Committee, 28 July 1851, p. 223.

- L. J. Smith, Challenge and Change. The St. Peter’s Schools Newton-le- fVillows 1860-1960, 1960, pp. 8-9.

- Winwick Rectory Act, 4 & 5 Vie. Cap. 9.

- F. E. Cooke, Newton-in-Makerfield Parish Church 1843-1943, 1943, p. 10.

- Bryan Morgan, Railways: Civil Engineering, 1971, p. 33.

- Mr Hodgson was a director of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company.

- Christina Colvin, Maria Edgeworth. Letters from England 1813-1844, ‘971, PP- 4l8~20.

- Minutes Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company Meeting of Directors, 27 January 1827, p. 44.

- C. Wilson, ‘The Entrepreneur and the Industrial Revolution in Britain’, Explorations in Entrepreneurial History, 1st ser. 7 (1955), 132.

- H. J. Fleure, Some Problems of Society and Environment, Publication No. 12, Inst. Br. Geog., 1947, p. 29.

Transcribed by Steven Dowd from the original essay written by Lynton ]. Smith, M.A., B.Litt. (Oxon), M.A. (Lond.). This version @Steven Dowd 2023